This post is about 3 women who paint at a place called Wirrimanu or Balgo, in northern WA, Australia: Dulcie Nanala, Jane Gimme, and Sadie Paddoon. I could have written a post about each of them or indeed any of the other thirty or so artists from the Warlayirti group who are connected to the art centre at Balgo, and maybe one day I will. Here, however, interwoven with their work, is a tiny look at the three painters who depict the world around them in captivating style.

Strikingly unique, each artist creates a map that takes them onto country and back, that leans on their knowledge and provides sustenance for those lucky enough to see their work. Unmistakably true to their vision, the work of these artists rests on a vast subtext, a metaphorical, allegorical, symbolic and literal connection that draws the onlooker in and makes them want to know more. Standing in front of the work, I get the feeling it describes a trust in homeland and landscape and country and self, that I, with my white eyes, am wanting of. These works have helped me to see into a paradigm of Australia, that despite having lived here all my life, I feel I have never known.

Dulcie Nanala’s canvases are vast but particular, enormous but precise. It is as if she is looking down from a great height onto the land with a colourful eagle-eye. Her work, for me, is dynamic in the way the landscape is dynamic. Through it I can read the differences in contour and curve, outline and form. So deftly executed, this scene above creates its delicate differences in a luminous celebration. The country Dulcie has painted here is that around Wilkinkarra (Lake Mackay) with its claypans and salt lakes and sandhills. And it is her interpretation of this land that gives us the opportunity to not only see it but to feel it as if, through her eyes we are given access.

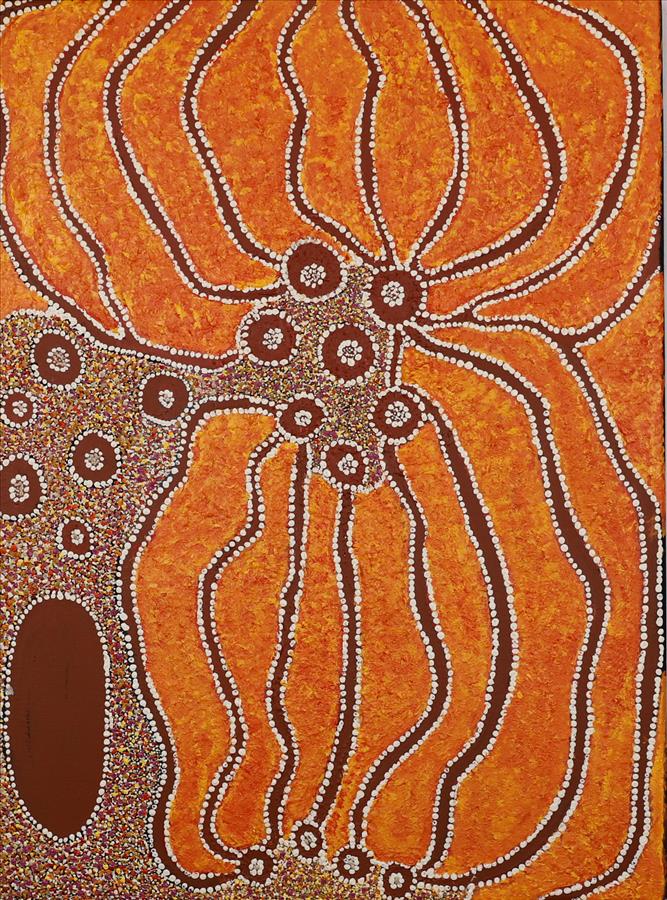

Jane Gimme paints her mother’s country, Kunawarritji or Well 33 on the Canning Stock Route. Here she depicts the tali (sand dunes) which dominate the landscape of the area, with the tjurrnu (soakwater) at the edge. Other circles depict holes where the ancestral spirit dog, Kinyu, lives with its pups. During hard times when there was no kuka (meat) or mangarri (vegetable food) the old people would ask Kinyu for food.

The richness in this work creates a vibrance that’s difficult to turn away from. The palpable assuredness holds us to its energy and configuration. Through its colour and line we are bound to an earthly beauty that nets us in calm rhetoric, showing us a belief in country we didn’t know we were missing. The clarity of this work is visceral and so we look, wanting to absorb its form and digest the trust it generates.

Sadie Paddoon has depicted some of her TjaTja (grandmother’s) country called Ngantalara. A long time ago her people used to walk this country looking for the rockholes for water, but they couldn’t find them. They started burning the dry grasses across the soak plain so they could navigate that country in the future. These squares represent the burnt patches, the white ash and red earth.

Sadie’s work is counterintuitive. To look at squares and see life’s amoebic quality, feels, on a surface level, not possible. But the further an artist can abstract their world into meaning then the farther they can take the viewer into understanding. It is as if, especially in Sadie’s case, the painter is an interpreter to the language of country which she makes no excuses for having in her heart. We know it when we see it. An authentic trial of intrinsic meaning. This is why we want to celebrate with her, and all three women. Their work calls for us, the viewer, to do it. And, like a feedback loop, we begin to learn a little of what they know.